If you’ve ever tapped an ID or payment card on a reader, been through a contactless toll gate on the highway, or even gone shopping for clothes at the mall, then you have experienced the wonderful technology known as RFID.

An abbreviation for radio-frequency identification, RFID might feel like a distinctly 21st-century technology, but it actually has a fairly long history, with its earliest known predecessor dating back to 1945. It all started with a Soviet espionage device that used external radio signals to power a passive audio signal transmitter. In other words, a bug. It was invented by Leon Theremin, the same inventor of the Theremin, a funky musical instrument.

Essentially, RFID is a form of wireless data transfer that utilizes radio waves. It’s a very efficient data transfer system for certain applications due to the almost instantaneous speed and the relatively small size and low price of its components. Modern-day RFID uses are highly varied. From the logistics, retail, agriculture, transportation, veterinary, and IT industries to institutions like libraries, office buildings, and even racing events.

Well, we can start by breaking it down into its three main components. These are the RFID tag, RFID reader, and antenna. In a nutshell, it’s a simple matter of the RFID reader scanning the chip embedded in the RFID tag, retrieving its data.

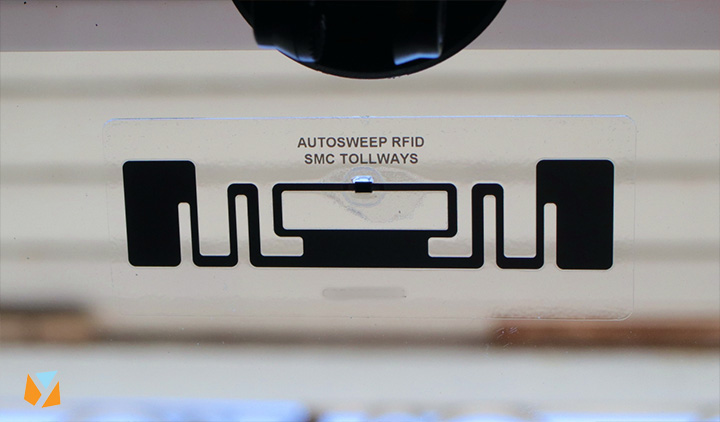

Photo by: Philkotse

These two components interface with each other using antennas. You may have noticed that RFID tags and stickers have either a squared-off spiral or zig-zag line. The RFID reader sends a radio wave of a certain frequency, depending on the use case. The RFID tag antennas accept this radio wave as energy, which then powers up the chip. Once the chip is powered up, it sends back its own radio waves through the antenna back to the reader, which interprets this as data. This is the basic theory behind RFID technology.

Depending on the real-world application, the process can be scaled accordingly. For example, different frequencies can be used to extend or shorten range, the tags can be actively powered for a constant stream of data exchange, and the chips can have different amounts of data.

Storage capacity varies from chip to chip, but the most commonly used types can store up to 2kb. This doesn’t sound like much and is definitely one of RFID’s limiting factors. However, this is usually more than enough for its modern-day usage.

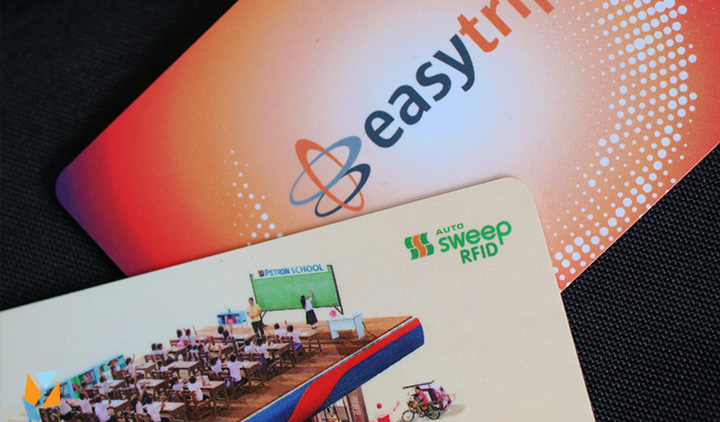

Let’s use ETC (electronic toll collection) systems in highways such as Autosweep and EasyTrip as an example. When you drive your vehicle forward towards the toll gate and the RFID reader interfaces with the RFID sticker attached to your headlight or windshield, the system only needs to know a couple of things. It only needs to know which entry point you came from and who you are. Based on these two data pieces, the system will know how much money to deduct from your account. The best part is, the whole process happens in less than a second, barring any connectivity or system issues.

Same thing with the security tags you see in clothing stores. When one of these tags enters the boundary of the anti-theft gates at the front of the store, only a minimal amount of data is exchanged. The mere presence of the security tag within the gates already tells the system all it needs to know — an attempt has been made to steal this particular item of clothing.

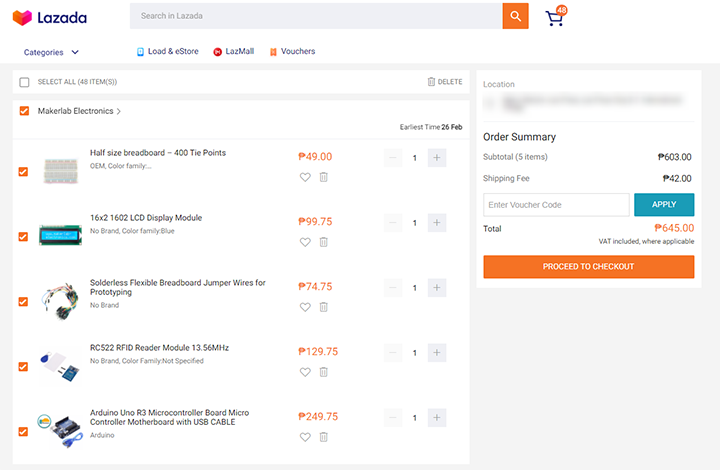

Perhaps our favorite thing about RFID is just how easy it is for the average person to get into. The low cost we mentioned earlier is also true for DIY purposes, with a basic set of components (Arduino, RFID reader module, RFID tags, LCD, breadboard) only costing around PHP600USD 10INR 867EUR 10CNY 74. A wide variety of home electronics projects can benefit from RFID technology, and it is a cool way of learning more about it.

However, after all, is said and done, all of the RFID technology we use today would not exist without one man — the late American inventor Charles Walton. Credited as the “Father of RFID,” Charles Walton’s 1983 patent was the first to use the term. He actually passed away in 2011.

YugaTech.com is the largest and longest-running technology site in the Philippines. Originally established in October 2002, the site was transformed into a full-fledged technology platform in 2005.

How to transfer, withdraw money from PayPal to GCash

Prices of Starlink satellite in the Philippines

Install Google GBox to Huawei smartphones

Pag-IBIG MP2 online application

How to check PhilHealth contributions online

How to find your SIM card serial number

Globe, PLDT, Converge, Sky: Unli fiber internet plans compared

10 biggest games in the Google Play Store

LTO periodic medical exam for 10-year licenses

Netflix codes to unlock hidden TV shows, movies

Apple, Asus, Cherry Mobile, Huawei, LG, Nokia, Oppo, Samsung, Sony, Vivo, Xiaomi, Lenovo, Infinix Mobile, Pocophone, Honor, iPhone, OnePlus, Tecno, Realme, HTC, Gionee, Kata, IQ00, Redmi, Razer, CloudFone, Motorola, Panasonic, TCL, Wiko

Best Android smartphones between PHP 20,000 - 25,000

Smartphones under PHP 10,000 in the Philippines

Smartphones under PHP 12K Philippines

Best smartphones for kids under PHP 7,000

Smartphones under PHP 15,000 in the Philippines

Best Android smartphones between PHP 15,000 - 20,000

Smartphones under PHP 20,000 in the Philippines

Most affordable 5G phones in the Philippines under PHP 20K

5G smartphones in the Philippines under PHP 16K

Smartphone pricelist Philippines 2024

Smartphone pricelist Philippines 2023

Smartphone pricelist Philippines 2022

Smartphone pricelist Philippines 2021

Smartphone pricelist Philippines 2020